Apologies for the radio silence. While I’m not one for excuses, I think I have a decent one here.

Regular readers may remember that, back in January, I wrote about cyclists and bone health. In the intro, I snarkily pointed out that there are two kinds of cyclists: those who have broken their collarbones and those who will soon break their collarbones.

Last month, life imitated snark. I made the transition from the latter to the former with a distal clavicle fracture.

Steep? Sandy? Littered with rocks? I got this!

While it’s standard to blame others when you crash (“It was the tree’s fault!”), this broken bone was 110% my doing. Marilyne and I were exploring new trails in Palos Verdes on our CX bikes and I figured I had the mad skillz to descend a particularly steep, rocky grade.

This assumption was incorrect. Had I been on my mountain bike, with its forgiving suspension and chubby tires, I might have been able to plow through the surprisingly loose dirt and obnoxiously pronounced stones, but the skinny tires and rigid frame of my CX bike weren’t having it. I skidded across the sand until I hit an especially big rock head-on and endoed over the handlebars.

Falling is basically a lifestyle choice for me. I’ve been known to fall over while standing still, so imagine how many times I’ve fallen off of a bike. This time was different. The moment I touched down on my shoulder, I knew something was wrong. As I ragdolled off various rocks for another twenty feet, two things went through my head: “This really hurts” and “Crap! I dropped my sunglasses.”

Thanks to adrenaline and macho stupidity, I was able to get back on my bike, but I only made it a few miles before I realized I was not going to shake this off. I rode to the closest urgent care. At first, the doctor thought I’d just separated my shoulder. He ordered x-rays.

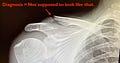

The technician took the first shot and declared, “Dude! You totally broke your collarbone—oh, uh, I’m not supposed to tell you that, but you’re about to find out anyway.”

The doctor will see you now.

A painful, crabby week of being slapped around by my HMO later, I got in to see my orthopedic surgeon. I say “my” orthopedic surgeon because Dr. Huber has repaired both my rotator cuffs, my left hip, and Marilyne’s collarbone. We joke that the Faye family has put his kid through college.

Dr. Huber—who I could probably call Glen at this point if my midwestern upbringing allowed it—wandered into the exam room, eyes on my chart, assuming I was there as a follow-up regarding the rotator cuff he’d Frankensteined back together a year ago.

“Hey, Denis. How’s it go—WHAT THE HECK?” he blurted out as he glanced up to see the x-ray of my cracked collarbone.

Another semester, paid for.

A distal clavicle fracture happens closer to the shoulder joint than most fractures. As you can see from the first photo, it was displaced, meaning the two parts of the bone no longer touched. Dr. Huber told me that these types of fractures often don’t heal correctly. Also, there’s a chance that bone might have worked its way through the fascia and pop out of my shoulder. Indeed, I could feel it grinding around in there and I have no desire to become a character in a David Cronenberg film, so we agreed a plate would be the best option.

Between you and me, I’m kind of excited. Steel plates are cool—and now Marilyne and I have a matching set. (She broke her collarbone in a bike race several years back and opted to leave the plate in.)

What I don’t like is this stupid sling I need to wear and the fact that I can’t ride or run for at least another couple weeks. This will greatly reduce my daily exercise-induced calorie expenditure, which brings us to today’s topic—what (and how much) should you eat when healing from injury?

I am not a doctor. I just play one on the internet.

First things first, I’m about to walk the line on medical advice here, so please remember, I’m not a doctor. That said, everything I’m saying is based on research done by PhDs—and links are provided. But still, my observations should never trump what your doctor tells you.

That said, if your doctor doesn’t agree with me, you should probably talk to another doctor because this is all pretty common sensical and grounded in legitimate science.

Bone-friendly nutrients.

This previous NPB column explains bones pretty well, so please start by reading that. Even when you’re perfectly healthy, your bones are in a constant state of breaking down and rebuilding. Breaking a bone means your body will need to step-up the rebuilding part, so make sure to get all the right micronutrients. That means calcium, because there’s a lot of calcium in bones. Vitamin D helps absorb calcium. Magnesium helps absorb vitamin D. Vitamin K2 helps calcium move through your system.

Those are the big ones. A 2019 article in the journal Sports Medicine features a much larger nutrient shopping list, including the ones above as well as phosphorus, zinc, copper, boron, manganese, potassium, iron, vitamin C, vitamin A, B vitamins, and silica. So, like, most of the micronutrients.

While you’re at it, don’t forget protein. In addition to all those minerals, bones are about 30% protein, so you need those amino acid building blocks.

Frankly, you’ll probably lose your mind trying to track down all these nutrients. Instead, focus on a balanced diet filled with protein, whole grains, and lots of produce—at a sufficient calorie level, which brings us to our next point.

Just eat.

Healing from injury is not a time for weight loss. I know the temptation is to drop calories since you won’t be exercising, but this is a terrible idea.

According to a 2009 article in the journal Eplasty, healing from a big injury—broken bones and/or surgery, for example—burns quite a few calories. I’m not typically a calorie calculator guy (although Lord knows I dealt with enough of them during my time at BODi), but let’s use some math to put this into perspective.

A standard way of determining your daily caloric burn is to figure out your resting metabolic rate (RMR)—the amount of calories your body burns before any activity—using a calculation like Mifflin-St Jeor. Then you multiply it by an “Activity Factor” ranging from 1.2 for light activity to 2.1 for super intense activity.

If you’re in injured, you need to include a “Stress Factor” ranging from x1.2 for a minor injury to x1.5 for bone fracture, severe wound, or severe burn.

So, let’s say that your RMR—the amount of calories you’d burn if you spent the day in bed, immobile—is 1600 calories. Let’s add a high Activity Factor because you’re an active person—you trail run or cross-train most days, hard:

1,600 calories x 2.1 (Heavy Activity Factor) = you burn about 3,360 calories daily.

One day, you’re out running and some miscreant leaves a banana peel on the trail. You fall specularly—Instagram gold for the random lady who caught your wacky tumble on her phone, but terrible for you because you break your clavicle. (Just like me! Twinsies!)

You see the doctor, contribute to his daughter’s 529, have a plate screwed on, and you’re good—except you can’t run for at least three weeks. You can walk though. Yay! The Activity Factor for walking is moderate, so here’s your new math:

1,600 calories x 1.5 (Broken Bone Stress Factor) x 1.7 (Moderate Activity Factor) = you burn about 4,080 calories daily.

And if you have an indoor trainer so that you can Zwift as you’re healing, just imagine the caloric burn there!

Again, I’m not a huge calculator advocate, but even if it’s kind of right—a fair description of these calculators—that’s a strong indicator that you shouldn’t mess around with dieting.

The effects of undereating when bone healing are especially horrifying. Exhibit A: A 2004 study on young, exercising women demonstrated that, even without a break, bones don’t remodel as well when you undereat. (There’s more research like this. You’ll find it in that Sports Medicine article I referred to earlier.)

Exhibit B: Your body makes wound healing a priority over other functions. So, if you’re not getting enough food (especially protein), your body will autocannibalize what it needs from other lean body mass—that means muscle. It’s bad enough that you lose fitness because you can’t train properly. If you undereat, you also force your body to further break down muscle to heal.

Labor Day Blues.

I’m writing this on Labor Day. My wife just got back from the “Holiday Ride,” an event that takes place in Los Angeles on every major holiday. On Memorial Day, July Fourth, and Labor Day, it’s especially huge. Hundreds of cyclists—including most of my friends and nemeses—show up to ride together from Manhattan Beach to the top of Mandeville Canyon. Today was no exception. Marilyne tells me that they miss me. And I miss them.

Injury sucks. It messes with your head and causes you to make weird choices. While it may seem logical to add to your short-term suffering and lose a few pounds, it’s not. Cutting calories—and/or eating garbage—will inhibit healing, break down muscle, and end up creating long-term suffering.

If you want to get back on the road as soon as possible, go eat a sandwich.

Interesting article, Denis — thanks for this info, which helps to explain my fatigue after a recent injury.

Question: You mention that magnesium is an agonist for vitamin D, which of course is an agonist for calcium. But I'd read that magnesium is an antagonist for calcium — i.e., it inhibits absorption. Can you help parse that out? And, if you're looking for topics for future posts, I for one would appreciate an explanation of all the ways vitamins and micronutrients work with and against each other. Thanks!