Why Do We Cramp During Exercise?

Science isn't sure--but that doesn't mean you can't figure it out for yourself.

The Upshot, Upfront:

Lots of things, often in combination, cause exercise-associated cramping.

Experiment to find the nutritional cramp-busters that suit your unique needs.

Gentle stretching usually helps.

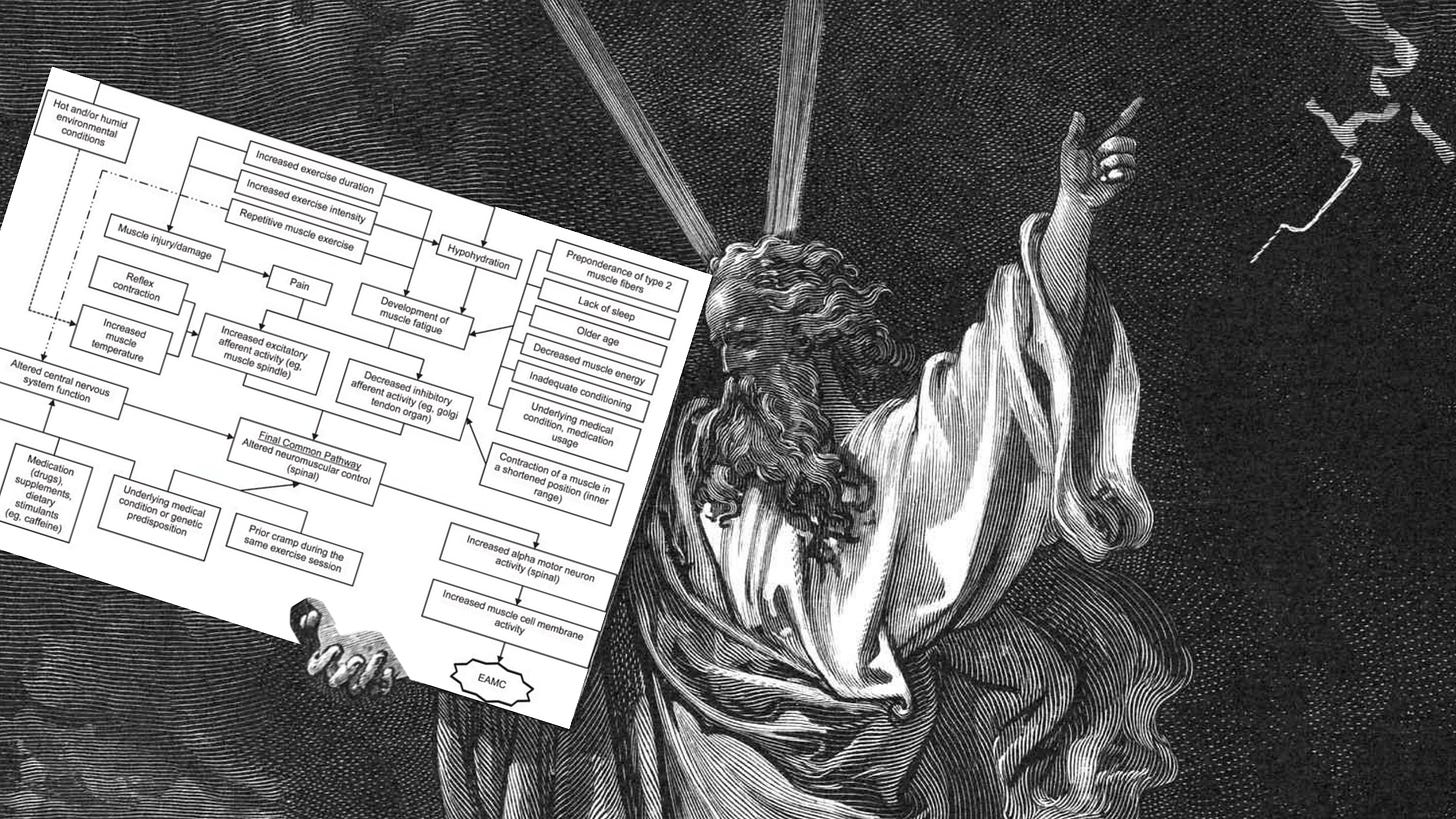

Is it just me, or do y’all get jazzed when you see a kick-ass flow chart?

Alright, fine. I’m weird, but still, if you’ve ever suffered from exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMCs), this chart could prove a game changer. You’ll want to laminate it and put it in your wallet. Or screenshot it to keep on your phone. Or tattoo it on your butt. Whatever you kids do these days to record important things for later reference, do that.

Despite the unpleasant omnipresence of EAMCs, science knows surprisingly little about them. One popular theory claims they’re caused by dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Another blames neuromuscular control breakdown due to fatigue.

Personally, I believe in a third path—the “multifactorial theory.” Put forth by Dr. Kevin Miller in 2020, the short version is that a bunch of crap can go wrong—ranging from fatigue to heat to dehydration to stress—and the resulting pathologic snowball leads to EAMCs.

That’s what this chart illustrates. The beauty of the multifactorial theory is that it validates the many harebrained cramping theories we athletes swear by, while simultaneously shaming us for being dogmatic about them.

Also, if you have cramping issues, this chart gives you a whole range of causes to investigate.

You can’t drink away a cramp.

I found the chart via a 2022 paper called “An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps.” It’s reasonably readable, as far as scientific papers go, discussing the causes of cramps as well as several possible solutions, including nutrition strategies, which can be summed up as follows:

Drinking water to rehydrate or hypotonic sports drinks to replenish electrolytes is fine, but don’t try to chug your way out of a cramp. Drinking too much (think gallons) can lead to hyponatremia—meaning you get too much water and not enough sodium so your cells swell up, causing your brain to expand and get squished by your skull. You have to drink a lot for this to happen, so don’t freak out. Just avoid having an “I’m gonna outdrink my cramp” mindset.

Bananas don’t really help in these situations because the electrolyte they contain, potassium, really isn’t “of interest” when you have cramps.

Pickle juice, ginger, vinegar, capsaicin, and other zinger shots are surprisingly effective. (Science calls them “transient receptor potential receptor agonists”) In one study, pickle juice worked 45% better than no fluids for clearing up a cramp. It worked 37% better than water. Given transient receptor potential receptor agonist don’t supply enough electrolytes to actually do anything, it’s unclear why they work. One theory is that the “oropharyngeal reflex” they cause inhibits cramps. So, basically, whatever made you grimace when you knocked back that Hotshot also made your muscles forget they were cramping.

The review concludes that the best thing you can do for a cramp is gentle stretching—although they had me at pickle juice. Anything that earns a grimace is a-okay in my book!

Your cramp prevention solution is completely right—and completely wrong.

The review also discusses various nutrition techniques for preventing cramps. While no one denies the importance of proper hydration during long efforts, when it comes to cramp prevention, studies investigating sports drinks, salt pills, and all the rest are packed with qualifiers like “may,” “could,” and “warrants further investigation.”

Over the years, I’ve been cornered by many a well-meaning, alpha-rube cyclist assuring me that his salt pill or cinnamon shot is an elixir of the gods, guaranteed to cure all that ails me—most notably cramps.

The EAMC chart validates these well-meaning Professor Harold Hills on Wheels—in the sense that their solution solved their problem. With so many combinations of things that can cause cramping, it stands to reason that different solutions work for different people.

The chart also illustrates why science struggles to pin down a catch-all solution for cramping. No matter what Connor MacLeod tells us, there can’t be only one.

The quest for foods and supplements to alleviate EAMCs is a sterling example of “personalized nutrition”—the idea that we all have unique physiologies so we require unique nutrient solutions. If you’re a cramper, I encourage you to give this chart some hard thought. Try to figure out which boxes might apply to you. Once you’ve narrowed it down, explore strategies that make sense to your specific situation.

When you find it, feel free to share here!

Another well written and interesting article!

exercise-induced muscle cramps (EAMCs) ?

Shouldn't that be EIMCs ?